By Andrea Gagliarducci

VATICAN CITY, 11 October 2022 / 10:00 AM (ACI Stampa).

From the meetings of the conciliar fathers, a network of bishops was born with a small note that already looked beyond the Iron Curtain and has now become the Council of the European Bishops’ Conferences.

The then Monsignor Roger Etchegaray called it “a simple note”. And perhaps this simple name was appropriate, if you look at the size of that document: two pages, typewritten, and divided into very quick and agile points, making a perfect summary of the thought of those days. Yet, from that small note an inspiration was born that which would lead to the formation of the Council of European Bishops’ Conferences, a network of presidents of the Bishops’ Conferences of Europe that today looks towards a united and visible Europe under the Christian banner, from the Atlantic to the Urals, beyond divisions and even beyond a war that is now at the heart of Europe.

After all, that was probably the idea of St John XXIII when he convened the Second Vatican Council sixty years ago. A builder of bridges, apostolic delegate to Bulgaria and Turkey and Nuncio to Paris, a connoisseur of the two lungs of Europe like few others (and it is no coincidence that the Bulgarian Exarchate is named after him), John XXIII envisaged a Council that would be ecumenical and, in the end, an opportunity for the Church to encounter, to renew itself from the bottom up.

But – and this is the resounding fact – not in a political – doctrinal sense. The idea was not to change doctrine, but to rebuild the Church, to go beyond walls, beyond divisions, to look to a reconciled world; reconciled in the light of the Gospel. A world in which everyone would be the Church, and the Church belonged to everyone.

It was a new, open climate. A climate in which meetings were taking place. It was a synodal Church without the term being yet abused, and without even the Synod of Bishops having been established (St Paul VI would do that at the end of the Second Vatican Council). It was a collegial Church, where initiatives were listened to and, if they bore fruit, were then institutionalised.

Thus, among the fruits of the Council, there is first and foremost the meeting of bishops from all over Europe, who pause to talk to each other, recount to each other their initiatives and begin to think that we need to do it more often, to do it constantly and continuously

It was a time of turmoil in Europe. First of all, there was the experience of reconciliation made by the Polish-German reconciliation letter, conceived by Cardinal Kominek, Archbishop of Wroclaw. Then, there was the experience of the worker priests. And then, there was the experience of the so-called ‘Churches of Silence’, there, beyond the Iron Curtain, persecuted, marginalised, even isolated.

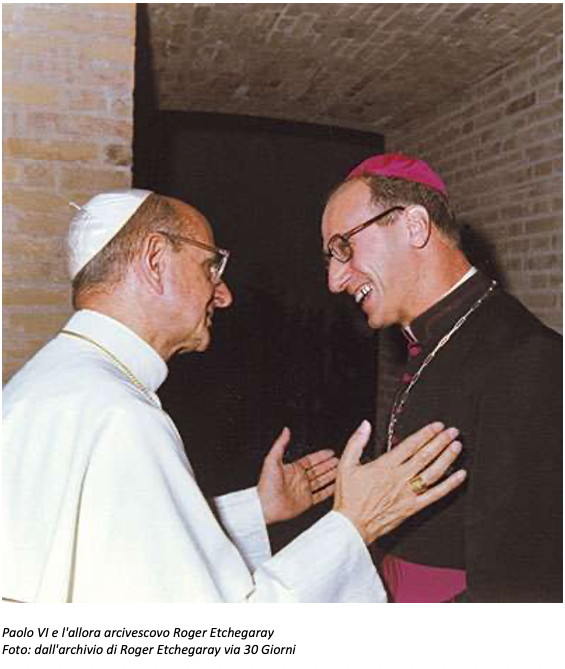

It was Monsignor Roger Etchegaray, then Secretary General of the French Bishops’ Conference, who took the initiative. He would later become, first, archbishop of Marseilles, then Cardinal and, as head of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, he would be the organiser of the Assisi meetings and John Paul II’s envoy to the most difficult places for the Catholic Church, from China to pre-Second Gulf War Iraq.

The “simple note” bears the date 4 November 1965. In those two pages, Monsignor Etchegaray highlights the multiplicity of exchanges that were taking place in Europe. He emphasises the need, which emerged from the conversations, to seek pastoral collaboration between the Bishops’ Conferences of Europe.

It is, writes Etchegaray, a note that “does not claim to be exhaustive”, nor does it seek “to be exclusive”, but rather it represents the wish that “a real effort be made to involve as many countries as possible in Europe”.

Europe considered as a geographical entity, from the Atlantic to the Urals, and therefore not as a political entity.

The inspiration to launch such an initiative draws strength from paragraph 5 of the Council Decree on the pastoral mission of bishops in the Church, Christus Dominus. We read in that paragraph: “Wherever special circumstances require and with the approbation of the Apostolic See, bishops of many nations can establish a single conference. Communications between episcopal conferences of different nations should be especially encouraged in order to promote and safeguard the common good”.

In what he calls “a pastoral note”, Etchegaray thinks of “two practical measures”: the establishment of a composite commission with delegated bishops, and the establishment of a regular exchange of information between the Bishops’ Conferences.

The Secretary General of the French Bishops’ Conference also makes an examination of the situation at the time. The free movement of workers allows “the multiplication of European exchanges”, but the 45 million “Europeans always on the move” who make up “the Europe of the vacations” should not be underestimated. And then, “for the past thirteen years, there has been a blossoming of European institutions leading to a growth of European officials”.

There is, in that ‘suggestive’ note – as Etchegaray writes in another passage – also the intuition that the increasing spread of Eurovision contributes to a European culture, together with the so-called European schools, which have flourished on the continent in various places, from Luxembourg to Italy via Belgium.

The note is prophetic about the problems to be addressed. First of all, “human, social, religious” problems “arising from labour migration”. But also, problems derived from a “contemporary atheism born of a technical civilisation”. And again “tourism and the mixing of peoples”, which unites with the “responsibility of the Christians of Europe in favour of ecumenism”.

Etchegaray also highlights the “possibilities and risks of the ever-larger presence of the Muslim world in Christian Europe”, and it was a theme that was innovative at the time, and extraordinarily topical today.

But the note does not fall on deaf ears. Etchegaray mentions a series of initiatives that had already developed in those years: the Episcopal Colloquium on the evangelisation of the working-class world in Tournai, which had been held in 1961 and 1962; the three European colloquiums on parishes (Lausanne 1961, Vienna 1963, Cologne 1965); the two Symposia on tourism (Lugano 1963 and Munich 1965) which had brought together 11 Bishops’ Conferences; the Congress on the formation of seminarians which had been held in Rothen, Holland, in 1964; the meeting of the editors of pastoral magazines which had been held in Freiburg im Breisgau in February 1965. Also noteworthy are the establishment of a European parish in Luxembourg; the birth of the Catholic Office of Information on European Problems in 1956 and placed under the authority of the bishop of Strasbourg; the various European secretariats.

These are the initiatives to start from in order to think of a “concerted pastoral care”, writes Etchegaray, which, however, avoids “creating a superstructure or an overly heavy body at the service of the Bishops’ Conferences”, and which places everything in the perspective of the universal Church.

This note gave rise to a series of meetings, until, in 1971, St Paul VI gave stable and institutional form to the Council of the European Bishops’ Conferences, the CCEE

This now has a history of fifty years, and over the course of five decades it has helped bishops all over Europe to speak out, in times of great crisis, but also of great inspiration, attempting to look beyond the times.

But the very presence of the CCEE tells us that the great fruits of the Second Vatican Council were, after all, dictated by fortunate and happy encounters, and by pastors sincerely interested in evangelisation, seen as a task and a mission.

A Council for a change of era, with pastors born to lead the way to that change of era. Today, it is a different, yet similar Europe. A Europe that still owes much to that simple note born not from the formal meetings of the Council, but from the informal gatherings of those who participated in the Council. It was truly an outgoing Church.